The Paradox of Automation

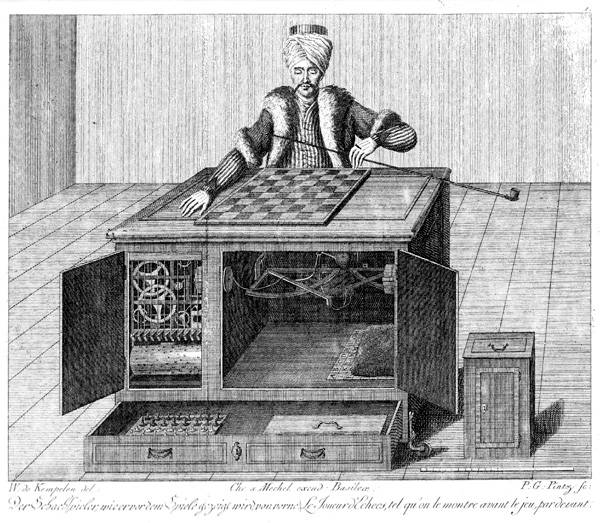

In 1770, an intriguing invention captivated the world: the Mechanical Turk, created by Wolfgang von Kempelen. The automaton was a life-sized figure dressed in Ottoman robes, with a turban and a pipe in its mouth, that appeared to be a marvel of automation.0 It played chess against humans and won most of the time.

However, the real magic was not in gears or levers but in the human chess master concealed within. Kempelen designed the machine so a person could fit inside the box and control the Mechanical Turk's arms and hands. They could see the board through a system of mirrors and use a series of levers to control the arms and hands of the Turk to make its moves.

It was so convincing that many people thought the machine could actually play chess on its own. Additionally, the audience could chat with the machine using a peg board to spell out messages, which the concealed human could then respond to by moving the Turk's head to indicate "yes" or "no." The Mechanical Turk was a sensation during its time, inspiring many other inventors to create similar automata.

Fear of automation dawns

The Mechanical Turk, a marvel of the late 18th century, fascinated audiences without sparking fears of job loss, despite its presentation as an automated chess player. Nobody seemed concerned for the plight of the displaced professional chess player.

The arrival of the 19th century marked a stark contrast in public perception towards technological advancements. The fascination with marvels like the Mechanical Turk gave way to apprehension and resistance as the realities of the Industrial Revolution set in.

One of the most emblematic movements of this era was the Luddites. This group of English textile workers, responding to the threat of their skills being rendered obsolete by mechanization, resorted to destroying weaving machinery. Their protest was less about the technology itself and more a backlash against an economic system that leveraged these machines to undermine their livelihoods and well-being.0

This period of industrialization saw not just the Luddites, but also other significant protest movements. Workers increasingly recognized that the rapid pace of mechanization and factory production was reshaping the job landscape dramatically, often at the expense of skilled artisans.

The Luddite movement was therefore part of a broader wave of resistance across England, where similar sentiments were echoed in various industries facing automation. In the United States, similar responses emerged in the early 20th century, with notable protests by elevator operators against the introduction of automatic elevators, reflecting a universal concern over job security and the preservation of traditional skills.

These movements highlighted a growing awareness and apprehension about the redistribution of wealth and job displacement caused by automation. They underscored a critical aspect of technological progress – its potential to create winners and losers, and the vital role of economic systems in determining who benefits and who bears the cost.

Two schools of thought on job automation

Later in the 20th-century, emerging economic theories delved into the complexities of technological progress and its varying impact on employment. John Maynard Keynes' essay "Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren" (1930).0 introduced the concept of "technological unemployment," expressing concern over the potential of technology to displace human labor across various industries. His theory delved into the societal and economic ramifications of such a shift, contemplating a future where machines could significantly diminish the role of work in human life.

In contrast to Keynes' apprehension, Joseph Schumpeter presented a contrasting viewpoint in his 1942 work, "Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy."0 Schumpeter's theory of "creative destruction" painted technological advancements as a vital component of economic progress. He argued that while technology inevitably phases out some industries and job roles, it simultaneously catalyzes the creation of new markets and employment opportunities. For Schumpeter, each technological advancement was not just a disruptor but a driver of economic progress, fueling innovation and efficiency.

Does automation create even more work?

Interestingly, even if the Mechanical Turk of the 18th century had really worked, it wouldn't have reduced the number of jobs in the chess industry by eliminating human players. It would have created even more jobs than it replaced since nobody would have been able to operate one without a professional operator, who would need support from installers, maintainers, and craftspeople.

The idea of a service industry backing a network of Mechanical Turk installations mirrors a critical insight from cognitive psychologist Lisanne Bainbridge's 1983 paper "The Ironies of Automation": automation often doesn't reduce the amount of human effort overall; sometimes it creates more responsibilities for humans that are even more complex.0

Bainbridge's research showed that as systems become more automated, the human role shifts from manual operation to system monitoring and management. This shift is the paradox of automation: When we automate work, new tasks emerge for humans, which can be more complex than the original work. She pointed out that each new solution creates more problems, including automating away work. And that solving these new problems requires even more ingenuity than the original work. The march of progress creates increasingly complex work, even as it eliminates simple work.

Consider the case of Tesla's Autopilot system, a contemporary example that encapsulates Bainbridge's 1975 observations. While automating many aspects of driving, this advanced driver-assistance system doesn't fully replace the driver. Instead, it alters the driver's role, requiring continuous monitoring and readiness to take control.

Paradoxically, this can increase the driver's cognitive load, as they must stay alert and prepared to intervene at any moment. You're still responsible for not crashing the Tesla. You still have to pay attention. And now, instead of just driving, you have to also supervise an AI and make decisions about when to take control. Which is more complicated than just driving the car.

This irony of automation, where the tool designed to ease a task changes it in unexpected ways, highlights the evolving nature of human interaction with automated systems.

Modern technological shifts in employment

The story of job transformation in the wake of automation is nowhere more evident than in the case of telephone switchboard operators. Once central to communication, these operators saw their roles become obsolete with the advent of automated switching. Yet, this was not the end of their story. The telecommunications industry absorbed these workers into new, often more lucrative and satisfying roles like customer service, technical support, and network management.

This transition resulted in not just the preservation but the expansion of employment in the sector. More importantly, these new roles often offered higher pay, increased creative satisfaction, and a chance to develop advanced technical skills. The industry's growth post-automation led to a net increase in jobs, illustrating how technological advancement can lead to unexpected employment opportunities.

In banking, the introduction of ATMs in the latter half of the 20th century presents a similar paradox. While many feared that ATMs would lead to widespread job cuts for bank tellers, the reality unfolded differently. The efficiencies brought by these machines enabled banks to open more branches, particularly in rural and under-served areas, where banking services and jobs were both needed.

This expansion did not result in fewer teller jobs; instead, it created more teller jobs in more places. The nature of these roles also evolved from simple cash transactions to involve customer relations, financial advice, and sales, offering a more diverse and engaging work experience. This scenario in banking is a prime example of how automation, contrary to diminishing employment opportunities, can catalyze job creation and economic development in new areas.

The banking scenario demonstrates how automation can catalyze job creation and economic development in new areas. Similarly, in 2024, major fast food chains like McDonald's and Shake Shack reported that their self-service kiosks, rather than eliminating jobs, have created new roles and increased overall efficiency. These kiosks have shifted labor from traditional cash register tasks to new positions such as "guest experience leads," who assist customers with the kiosks and enhance their ordering experience. The kiosks also effectively upsell items, increasing sales and allowing staff to focus on food preparation and customer service rather than on processing transactions. As Shake Shack CEO Robert Lynch noted, kiosks ensure that upsell opportunities are presented to customers, which can be overlooked during busy periods.

This shift in responsibilities illustrates how automation can lead to the creation of more diverse and engaging job roles, much like the transitions seen in telecommunications and banking.

The experience with kiosks provides valuable lessons for the industry as it explores further automation, such as AI in drive-thru lanes, reinforcing the idea that technological advancements can lead to unexpected employment opportunities and a more dynamic workforce.0

Recent developments in enterprise software further illustrate this trend. Salesforce, a leader in customer relationship management software, is pivoting its AI strategy to include autonomous agents capable of handling tasks without human supervision. While this might seem to threaten jobs, Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff frames it as a way for companies to increase workforce capacity during busy periods without hiring additional full-time employees. This approach reflects the complex reality of AI's impact on employment - potentially reducing certain roles while creating new opportunities and ways of working.0

Postmodern technological shifts in employment

These historical examples demonstrate how automation has traditionally reshaped industries, often creating more jobs than it eliminated. However, the current wave of AI and advanced automation presents unique challenges and opportunities that go beyond these past patterns. Let's examine how these postmodern technological shifts are impacting employment in ways both similar to and distinct from their predecessors.

According to a report from ResumeBuilder, 37% of business leaders stated that AI replaced workers in 2023, and 4 in 10 predicted layoffs due to AI efficiency continuing through 2024.0 According to Asana's report on AI in the workplace, employees believe that 29% of their work tasks are replaceable by AI.0 And they're probably underestimating. We all can see that something big is coming.

But automating work doesn't mean less work for people. It can lead to more diverse kinds of jobs that are more satisfying, and it can lead to more jobs overall. The World Economic Forum's "The Future of Jobs Report 2020" estimated that AI could replace 85 million jobs worldwide by 2025 but also create 97 million new jobs in the same timeframe.0

Don't think you're immune

In the past, automation hurt jobs the most in sectors reliant on routine and manual tasks. The Brookings Institution has conducted several studies that challenge the assumption that only low-skilled, blue-collar jobs are at risk from AI. They argue that AI's impact on the labor market is more nuanced and widespread, affecting a variety of occupations, including those traditionally considered white-collar or high-skilled.

In one study researchers highlighted the potential for job displacement across a wide range of occupations due to advancements in Large Language Model-based systems (LLMs) like ChatGPT. This includes roles such as software developers and screenwriters, which are typically considered high-skilled, white-collar jobs.0 But now, software developers seem like archaic gatekeepers to app functionality, in a world where you don't need an app to solve problems.

Another study, used a novel technique to analyze the overlap between AI-related patents and job descriptions. The findings suggest that AI will significantly impact the work lives of relatively well-paid managers, supervisors, and analysts.0 And if you know any attorneys, advertisers, or radiologists, then you know people who are anxious about upskilling and pivoting careers.

This contemporary narrative of AI mirrors the past fears and adaptations seen during the Industrial Revolution. Just as society adapted to the sweeping changes of industrialization, creating new job opportunities and roles, AI's current and future impacts may similarly lead to a reconfiguration of the workforce, necessitating adaptability and a shift in skill sets.

Remember that automation creates more work

It's easy to focus on the jobs eliminated instead of the jobs created, but you can see the paradox of automation in the news today.

Amy Ingram is an artificial intelligence (AI) personal assistant launched around 2014 by the startup X.ai. (Not to be confused with Elon Musk's separate company X.AI, founded in 2023 with almost the same name.) The AI was designed to handle the task of scheduling meetings, taking on the mundane tasks of emailing and coordinating schedules. Users praised Amy for her "humanlike tone" and "eloquent manners".0

However, a controversy arose when it was revealed that there was an actual human behind almost every email sent by Amy. These humans, known as AI trainers, were responsible for ensuring that Amy didn't make mistakes that would reveal her to be a bot. The company advertised Amy as an AI personal assistant who could "magically schedule meetings," but the system wasn't yet ready to operate independently. AI trainers had to look over parts of almost all incoming emails to evaluate what Amy guessed the user meant.

Presto Automation Inc., known for providing AI technology to restaurants, is a prime example. Presto aimed to lower labor costs for their clients with AI-powered drive-thrus for fast-food chains like Checkers and Carl’s Jr.0 However, recent disclosures revealed that over 70% of customer interactions rely on off-site human agents.0 These agents, located in places like the Philippines, play a crucial role in ensuring the accuracy of orders, training the AI system, and refining its capabilities. Presto's automation technology eliminated some jobs, but it also created new ones. Both high-skill and low-skill jobs.

A recent Wall Street Journal article supports this view, suggesting that AI may not be the job killer many fear. The article points out that AI often generates more tasks for human workers than it eliminates. For instance, while AI can summarize vast amounts of literature, human experts are still needed to assess the output's reliability and relevance. Similarly, in programming, while AI can speed up initial code writing, human programmers are still essential for problem-solving, understanding customer requirements, and cleaning up AI-generated code.0

These cases reflect Bainbridge's paradoxical insights from her 1983 paper "The Ironies of Automation." As systems become more automated, human roles shift from direct operation to oversight and nuanced decision-making. These developments illustrate how automation, rather than simply reducing the workforce, often creates more complex responsibilities for humans.

So, what's your plan?

We do at least know a little about what's going to happen. Bainbridge's research about how automating jobs creates more work for humans tells us how to prepare. We can envision a future where jobs will revolve around monitoring automated systems and making high-level decisions about control, taking ultimate responsibility for outcomes where machines primarily do the work.

We know that automation will shift job requirements, increasing the value of soft skills such as creativity, judgment, and communication. We know that leveraging AI will be a critical skill in virtually any job. AI lives in a world of numbers and is enabled by code, and those are both specific things you can learn. Software development might not be as common as a full-time job in the future, but working with code will still be a valuable skill. ChatGPT can answer your math homework for you but it doesn't replace math as a critical skill, because you're still ultimately responsible for solving your problems. Even if you have an AI coding assistant that understands trigonometry helping you to accomplish it.

The shift in how companies value and price AI capabilities also reflects these changes. For instance, Salesforce is moving away from traditional per-user pricing to a model where customers pay per AI-driven conversation. This change acknowledges that while AI might reduce the number of human users, it increases overall productivity and value. As a professional, understanding these new models and how they reflect the changing nature of work will be crucial. It's not just about learning to use AI tools, but also about understanding how they're reshaping business models and job roles.

What do you get paid for?

If you have a job, then are you paid to produce something? Words? Code? Billable hours? Safely-driven highway miles? QA ratings? Is your compensation based on how much you produce? If so, then your job is at risk of transformation regardless of what you do or how much education it took you to get there. If you're a cog in a machine and you work for a company that's marking up work to make a profit, then there is someone right now with a great idea for a viable way to replace you. If you're a junior associate at a law firm then your firm benefits in the short term by working you for billable hours but they win in the long term by replacing your cost entirely while providing the same services to their clients.

Is that why you have a job, though? You and your boss might see it differently. A lot of people think they get paid to work hard, but they really get paid based on how hard it would be to replace them. Because they're responsible for things.

We should all pivot toward that because taking responsibility is one of the last things that automation will ever be able to do. It's not a matter of technological progress in AI; it's a legal issue: The CEO can't put an unsupervised machine in charge of important things because that would be negligence. You can focus on increasing your capacity to be responsible for things that produce. And you can focus on being hard to replace. We know what kinds of skills our jobs will shift toward in the future and we can shift our capabilities now to prepare.

Even companies at the forefront of AI development recognize this dynamic. Salesforce, for instance, is developing AI agents capable of handling tasks without human supervision. While this might seem to threaten jobs, it's actually creating new opportunities. As routine tasks are automated, there's an increased demand for workers who can manage and optimize these AI systems, handle complex cases that AI can't solve, and develop strategies for integrating AI into business processes. These roles require a blend of technical knowledge and the uniquely human abilities to take responsibility, make high-level decisions, and navigate complex, unpredictable situations.0

In terms of the Mechanical Turk, don't focus on the chess player who it would have eliminated if the idea had been a viable business and if it had worked. Think about how much more work it would have created to build them. And install them. And advertise them. And sell them to people. Think about the industry of mechanics, machinists, toolsmiths that would emerge. And someone has to find financing for all of it. And deal with the liability issues. And technical writing. And...

We'll all be fine

Displaced workers will still be okay even if they don't consciously guide their fate and upskill. If you're a call center operator worried about being eliminated, fear not: you'll find future opportunities in data labeling and prompt engineering and other AI supervisory roles that will emerge that people can barely imagine now. The opportunities will arise even if you do nothing to make it happen. Your grandchildren will be okay whether they .

We can see from examples like the expansion of bank branches after ATMs that the new jobs won't all be for technologists. Burger-flipping robots won't just replace burger flippers. They will also create new low-skill jobs by enabling the fast food industry to reallocate its workforce. By allowing the companies to expand to more locations, burger-flipping robots could lead to more fast-food jobs for more people in more places. Chatbots that replace human operators create more jobs for humans to supervise the chatbots. Every industry transformed will see this redistribution effect, and nerds who know how to train AI models and their billionaire friends will not be the only winners.

So, if you're anxious about what's coming, focus on what you know will be necessary. As either a person or an organization, develop capabilities related to leveraging and monitoring artificial intelligence. And remember that society will be just fine. We don't know what will happen, but we know it will involve a lot of work. Don't worry, our grandchildren will have plenty to do.